The struggle unfolding in Venezuela is widely framed as a contest over democracy, sanctions, or the fate of Nicolás Maduro. In reality, it is better understood as part of a larger and more consequential competition: control over energy systems that underpin China’s economic power.

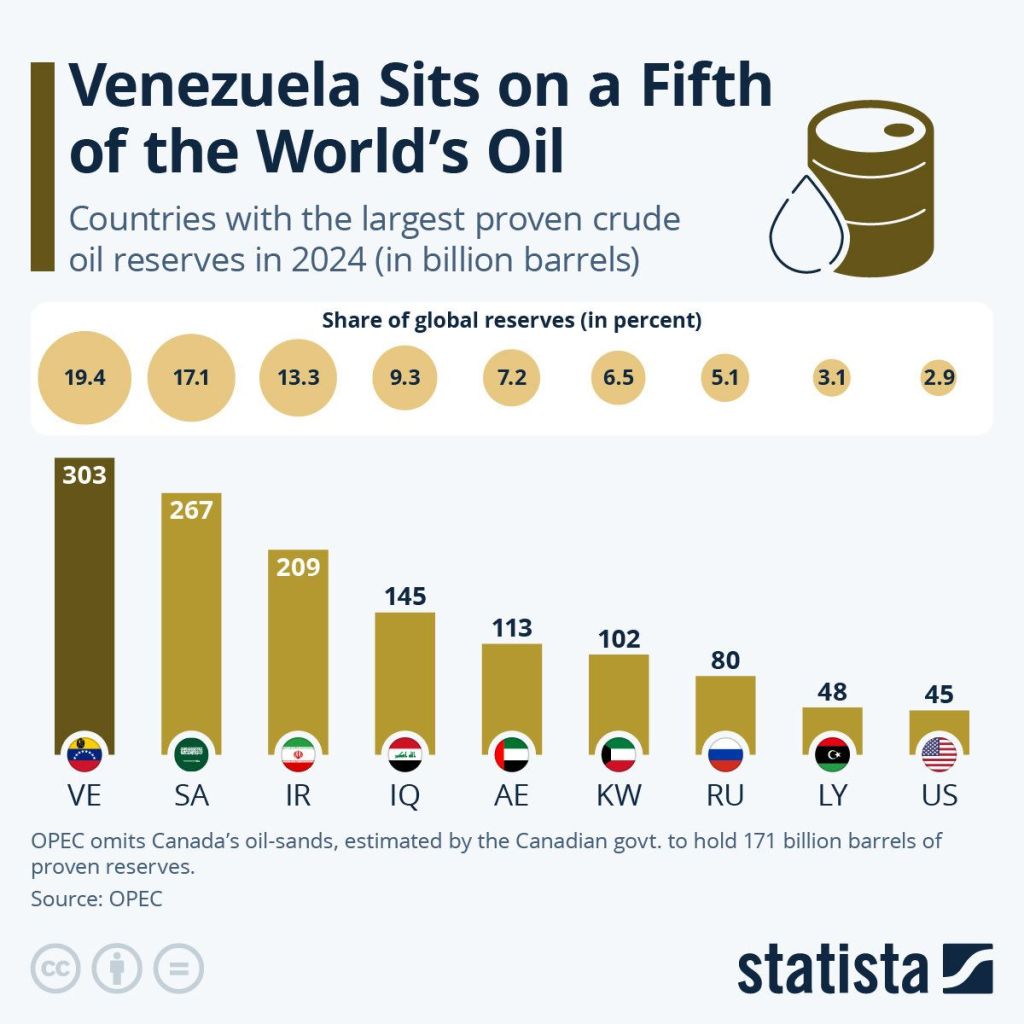

Venezuela matters not because of its politics, but because of its oil. The country holds the largest proven oil reserves in the world, roughly 300 billion barrels. For much of the past decade, China became Venezuela’s most important oil customer, purchasing crude at discounted rates and providing loans repaid in barrels. These shipments helped Caracas survive sanctions and gave Beijing something increasingly valuable: a reliable, low-cost energy source in the Western Hemisphere, largely outside U.S. influence.

Recent U.S. moves to reassert leverage over Venezuela’s oil sector therefore represent more than a bilateral policy shift. They signal an effort to pull a critical energy node back into Washington’s orbit — and, in doing so, to narrow China’s options.

Energy Power Is About Leverage, Not Volume

In strict numerical terms, Venezuelan oil accounts for only a small share of China’s total imports. But energy security is not about any single supplier; it is about diversification and resilience. Every barrel sourced from Venezuela is one that does not have to transit the Middle East or pass through vulnerable maritime chokepoints.

By weakening China’s access to Venezuelan crude, the United States does not cripple Beijing overnight. Instead, it nudges China back toward heavier dependence on regions and routes where Washington already holds disproportionate influence. Over time, that dependence compounds risk.

Energy power, in other words, is less about how much oil you control than about who feels pressure when disruption occurs.

Supply Means Little Without Transit

Oil is only as valuable as the routes that carry it. Here, geography does much of the strategic work.

Roughly one-fifth of the world’s oil passes through the Strait of Hormuz, and most of that oil is bound for Asia. China, Japan, and South Korea are the primary consumers. Any credible threat to Hormuz — whether from Iranian action or regional conflict — immediately spikes insurance costs, delays shipments, and injects uncertainty into Asian economies.

The United States does not need to close Hormuz to benefit from its vulnerability. The mere possibility of disruption acts as a pressure lever. China, by contrast, has limited ability to mitigate such a shock.

Further west, the Bab al-Mandab Strait forms another strategic chokepoint. Connecting the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean, it is essential for energy flows between the Middle East, Europe, and Asia. Conflict in Yemen has already demonstrated how fragile this route is; attacks on shipping have forced vessels to reroute around Africa, adding weeks and significant costs to global trade.

Taken together, Hormuz and Bab al-Mandab form a strategic vise. One threatens the source of Gulf energy; the other threatens its delivery. Both disproportionately affect import-dependent Asian economies — and particularly China.

Africa: The Quiet Contest

Beyond chokepoints, energy competition increasingly plays out across Africa.

China has invested heavily in African oil producers, ports, and infrastructure, including in Nigeria, the continent’s largest crude producer. Nigerian oil exports average over a million barrels per day and sit astride key Atlantic trade routes. Chinese firms finance ports and pipelines, but Western influence still shapes much of the surrounding ecosystem: security cooperation, maritime insurance, regulatory frameworks, and access to dollar-denominated markets.

This pattern repeats elsewhere. China builds physical infrastructure; the West often retains influence over the rules, financing, and security conditions that determine how energy actually moves. Control does not require ownership — only leverage at key points in the chain.

Asymmetry Is the Real Weapon

The strategic imbalance at the heart of this contest is simple.

The United States is now one of the world’s largest oil producers. It is relatively insulated from supply shocks that would severely damage import-dependent economies. China, by contrast, imports roughly 70 percent of its oil, much of it from regions vulnerable to geopolitical disruption.

This asymmetry creates freedom of action for Washington and constraint for Beijing.

If Hormuz closes, China’s economy slows.

If Bab al-Mandab destabilizes, shipping costs rise sharply for Asian trade.

If Venezuelan oil is redirected, China’s diversification strategy weakens.

The United States does not need to replace China as the buyer of every barrel. It only needs to increase friction — higher costs, longer routes, greater uncertainty. Over time, those pressures shape investment decisions, growth rates, and strategic behavior.

Venezuela as Proof of Concept

Seen in this context, Venezuela is not the centerpiece of U.S. strategy, but a test case.

It tests whether Washington can reclaim influence over an energy supplier that had drifted into China’s orbit. It tests whether this can be done incrementally, through market access and sanctions relief, rather than overt confrontation. And it tests how Beijing responds when diversification options quietly narrow.

If successful, the model is scalable. Similar dynamics can apply to other producers, transit hubs, and financing arrangements. The goal is not domination, but structural advantage.

Conclusion

This is not a new kind of power politics. It is a classic one, updated for a globalized economy.

Control the supply, control the transit, and you shape the system.

Control the system, and you influence outcomes without firing a shot.

Venezuela is not about Maduro. It is about energy, leverage, and the quiet mechanics of economic power. And it is unlikely to be the last place where this strategy is tested.

Venezuela is just the beginning.

Khaled Eibid